UPR: Background

The Universal Periodic Review (UPR) is an instrument that periodically reviews the human rights situations of all 193 UN member states. It was established in 2006 as the centerpiece of the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC). While other human rights bodies, such as the Commission of Inquiry (COI) and the Special Rapporteur, are investigative in nature, the UPR is designed to foster dialogue between states on implementing best human rights practices (Chow 2016). It does so by allowing each country to report on its own human rights situation, while also receiving reports from UN bodies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). By bringing countries that are typically reluctant to discuss their human rights record into the conversation, it complements the work of independent investigative bodies.

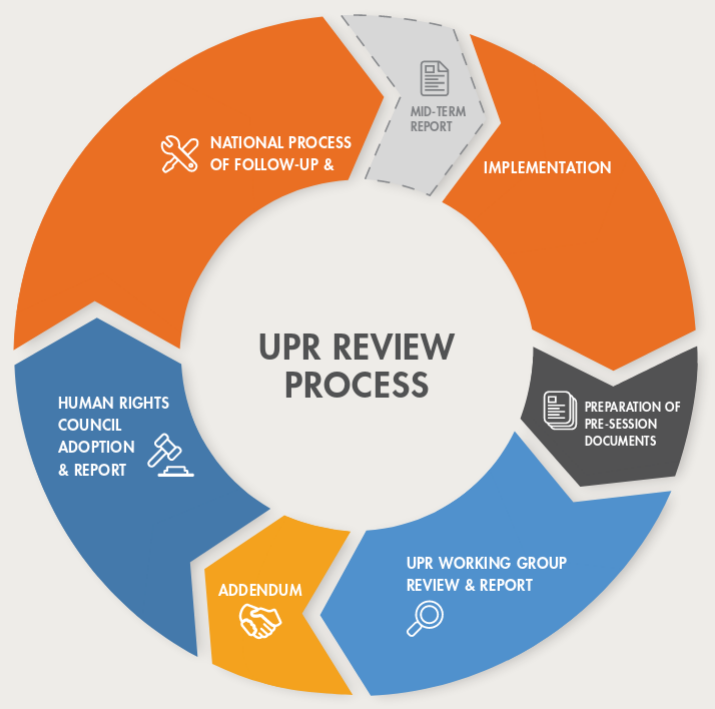

The UPR is structured so that states are reviewed in cycles, with each cycle taking 3-4 years to complete. In the first cycle (2008-2011), 48 states were reviewed per year. In the second (2012-2016), 42 states were reviewed per year. The UPR is currently on its third cycle (2017-2021). Reviews of each state are conducted by the UPR Working Group, which meets three times a year and reviews 14 states each session. The process for the UPR is made up of several steps, with several months in between each step:

Reports: The process begins with reports submitted to UPR Working Group by the state under review (SuR), UN organizations and treaty bodies, and NGOs. They describe the state’s current human rights situation and its progress in implementing recommendations from the last cycle.

Dialogue: A ‘troika’ of three states made up of UNHRC members facilitate a 3.5 hour ‘interactive dialogue’ between the SuR and UN members. Any UN state can make comments and recommendations to the SuR, and the SuR is given 70 minutes to respond to them.

Recommendations: The SuR looks over the recommendations and decides which ones it supports and which it ‘notes’. It is responsible for implementing the recommendations it accepts. The UPR Working Group submits an ‘Outcome Report’ to the UNHRC to be adopted at its next plenary (Chow 2016).

The responsibility to implement accepted recommendations falls on each respective state. The state is expected to provide updates regarding its progress in implementing recommendations during the following review. Nonetheless, the international community plays a role in providing requested assistance to Member States for the purpose of improving human rights conditions. While UPR recommendations are non-binding, meaning that there is no penalty for a state failing to implement them, the Human Rights Council will address cases where states consistently refuse to cooperate.

UPR Case Study: North Korea

As a UN member state, North Korea participated in the UPR, submitting its national report first in August 2009 and then in January 2014 (Chow 2016). During the first cycle, it received 167 recommendations from UN Member States, all of which it rejected during the following session. It was the only UN Member State to refuse to accept any recommendations in that cycle. However, in May 2014, after the release of the COI report and right before the second cycle of the UPR, North Korea belatedly accepted nearly half of the recommendations from the previous cycle. Although states typically either ‘accept’ or ‘note’ recommendations, North Korea included three more categories of its own: rejected “on the ground” because they “slandered the country”; considered but rejected; and partially accepted. In the second cycle, after North Korea received 268 recommendations, it applied its own system of categorization onto them, ultimately accepting 113 recommendations.

Examples of recommendations that North Korea outright rejected are: putting an end to punishing “activities against the State or society”, closing prison camps, and any other recommendations that echoed the sentiments of the COI and Special Rapporteur. Recommendations that North Korea considered but rejected are: eliminating sanctions against defectors, permitting independent journalism and media, and legalizing markets. Several noted recommendations are: improving the treatment of prisoners and ending forced labor. Partially accepted recommendations include: conforming with international standards of justice and submitting treaty implementation reports to the UN on time. Lastly, accepted recommendations mention: improving the rights of women and children, ratifying signed treaties, and making public services more accessible.

While there are several possible reasons that North Korea chose to engage with the UPR, despite the fact that it had rejected other human rights mechanisms, one reason that stands out is the publishing of the COI report. After the COI reported grave human rights violations within North Korea, challenging the legitimacy of the government, North Korea reacted by publishing a 100-page report (through the DPRK Association for Human Rights Studies) denouncing the COI’s findings. It also suddenly accepted some of the recommendations from the previous cycle, three years after the deadline had passed. This suggests that investigative mechanisms, such as the COI and the Special Rapporteur, complement more interactive and non-confrontational mechanisms like the UPR. While it may be true that North Korea is possibly using the UPR to boost its international reputation by nominally accepting certain recommendations, as the UPR has no monitoring component and, as such, has no way to prove a state’s compliance, is also true that its reports create a standard by which its human rights progress can be measured (Chow 2016).

Reference

Jonathan T. Chow. “North Korea’s Participation in the Universal Periodic Review of Human Rights.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 71, no. 2 (2017): 146–63.

Last Updated: July 24, 2018

Author: Sarah Kim