Background to the ECCC

The Khmer Rouge (KR) regime ruled Cambodia from April 1975 until December 1979. Under Pol Pot’s leadership, approximately 2 million people – a quarter of Cambodia’s population – died in mass executions and from starvation, disease and torture in the dire conditions of labor camps. Even after the regime was ousted by Vietnamese forces in 1979, it continued to threaten the Vietnamese-backed Cambodian government, thanks to the support of China, the US and most western countries. The UN even permitted the KR to represent Cambodia in the General Assembly until 1982, despite the fact that it no longer ruled Cambodia at that point.

In 1997, the Cambodian government requested the UN’s help in establishing a trial to prosecute KR leaders. In 2006, the ECCC was established as a hybrid court in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, with Khmer as its working language. Nominally it was a Cambodian court, but in practice, it operated independently of the Cambodian judicial system. The agreement that established the ECCC provided for a majority of Cambodian judicial personnel, with a formula designed to resolve disagreements between international and national co-prosecutors and judges. While its broader purpose was to ensure that the tribunal upheld international standards, its effectiveness in preventing undue interference on the part of the Cambodian government was limited, despite its clause that allowed the UN to pull out under such circumstances. In terms of funds, international donors supplied 90% of the total amount, with the Cambodian government responsible for the remaining 10%.

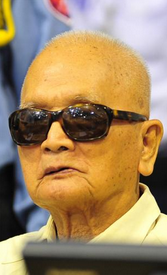

Nuon Che

Khieu Samphan

Kaing Guek Euv

The ECCC’s purpose is threefold: 1) To ensure accountability for crimes committed by the KR regime between 1975 and 1979; 2) To improve the domestic justice system; 3) To enhance the general public’s understanding of what happened at that time. A total of four cases were opened. In Case 001, the ECCC convicted and sentenced Kaing Guek Euv, a.k.a. Duch, the director of the S21 secret prison, in 2010. In the most significant case, Nuon Chea, Pol Pot’s second-in-command, and Khieu Samphan, former head of state, were both charged with crimes against humanity and sentenced to life imprisonment in 2014. The second part of the trial also brought forth charges of forced marriage, genocide and sexual violence. Furthermore, the regime was accused of executing a deliberate policy of eliminating two ethnic groups: the ethnic Cham and Vietnamese.

The ECCC also pioneered methods of case procedure and management that were new to Cambodia. It set a precedent by allowing victims to play an active role in the trial as either complainants or civil parties. Complainants could inform prosecutors of relevant crimes that they believed had been committed. Civil parties were direct victims of the crimes committed and could apply to participate by supporting prosecution and seeking “moral and collective” reparations. The four cases combined had a total of 6,875 applicants. Their meaningful participation was ensured by the Victim Support Section, which also provided them free transportation to attend hearings.

There was tremendous public interest in the proceedings. By July 2017, over half a million people had attended the proceedings, and millions more had watched live television broadcasts. Needless to say, the ECCC succeeded in sparking public discussions about the past. Since 65% of the population had been born after the fall of regime, many had previously had a hard time believing that all these atrocities had actually happened. Thanks to the ECCC, the truth regarding the KR regime was brought to light.

Criticisms of the ECCC

As a hybrid court based in Phnom Penh, the ECCC inevitably faced criticism. One point of contention was that considering the amount of time and money invested into the ECCC, as well as the total number of perpetrators, the number of people sentenced was insignificant. Another major criticism was interference on the part of the Cambodian government. For example, while Cases 001 and 002 operated largely independently thanks to government approval, Cases 003 and 004 faced opposition because they were not in line with political interests. There were also allegations of financial corruption and influence over witnesses that had ties with the government. Additionally, a broader criticism was that the ECCC seemed to do little to transform Cambodia’s current culture of impunity for politicians. Other issues that the ECCC faced were inconsistent funding that constantly threatened to close it down and a lack of political support from abroad.

While these shortcomings are significant, they must also be considered in context. For example, the small number of convictions is partially a result of the delay in the ECCC’s establishment, since many alleged perpetrators, including Pol Pot himself, passed away before the tribunal. It should be noted that a sizeable portion of the responsibility for the delay in the tribunal falls on the shoulders of the West, since they not only failed to stop the regime, but also supported its engagement in war with Vietnam. Furthermore, while the ECCC was certainly imperfect, its significance to victims should not be overlooked. As Olsen, a spokesman for the tribunal, said, “What the harshest critics often tend to forget is that the alternative to the ECCC is not a perfect tribunal, which would serve as a beacon of light in the world of international justice. On the contrary, the alternative would have been nothing at all.” The ECCC left an overall positive legacy, in which history was preserved and a foundation for the rule of law established.

Key Lessons

The Open Society Justice Initiative is a human rights group that has monitored the progress of the ECCC throughout its operation. Below are several takeaways that they have recounted in their report- “Performance and Perception” – that may be useful lessons for future hybrid tribunals.

- Do not delay. As Cambodia’s case clearly shows, the consequences of delay are less evidence, diminished memories, and fewer people to prosecute.

- Trials take a great deal of time and money once they begin. The judicial process cannot be confined to a political timetable. It takes time and money to identify, protect and sometimes treat witnesses. Amassing evidence, building a case and defending it is also a resource-intensive process.

- Streamline the process to maximize efficiency. Having acknowledged that trials are resource-intensive, streamlining the process from investigation and prosecution strategy to trial and appeal procedures is crucial. A court that is inefficient in its use of time and money both tests the patience of the population it seeks to serve and undermines its own credibility.

- Judicial action is more effective if it is rooted in local efforts at reform. The ECCC may have been more successful if it were both more firmly rooted in local reform efforts and if it served to build domestic capacity, strengthening Cambodia’s contemporary legal system. A strength of hybrid tribunals is that they can be used as powerful tools to build necessary domestic legal capacities, if this goal is integrated into the design of the court and expressed through dedicated funding and clear lines of responsibility at high levels in the court.

- It is a mistake to compromise on judicial independence. The ECCC’s effectiveness suffered because of the concessions it made to Cambodia’s Prime Minister, Hun Sen (a former Khmer Rouge commander), even though they appeared in the moment. UN expert opinions were ignored at times, and the groundless opposition towards further trials was not challenged.

Last Updated: May 28, 2018

Author: Sarah Kim